Table of Contents

Terminology

Virtualization-Based Obfuscation - A software obfuscation technique that transforms functions into custom virtual machines that emulate the functionality of the original code

Virtual Machine Entrypoint - A routine where the virtual machine is initialized, usually near the start of the virtualized function

Virtual Instruction - An opcode and optional operand that is tied to a certain operation within the virtual machine

Virtual Stack - A separate stack that is used solely by the virtual machine and manipulated through its instructions

Virtual Instruction Pointer - A counter that stores the location of the virtual instruction that is currently executing

Opcode Handlers - A routine that is tied to the execution of a certain opcode

Dispatcher - A routine that matches opcodes to their respective opcode handler

Context Variables - A location that holds data or a pointer to data that is essential to the execution of a VM (ex. Virtual Stack Pointer, Virtual Instruction Pointer, etc.)

Introduction

Welcome to the first part of my multi-part series on virtualization-based obfuscators. I've recently been fascinated by the complexity of these software protection solutions, so I spent my summer studying the architecture, internals, and functionality of some of the most popular virtualization-based obfuscators out there. I was able to do this research through a summer internship with the SEFCOM Lab at Arizona State University; I greatly appreciate their support and funding.

To give a quick introduction to the topic, software virtualization (and obfuscation in general) is generally the largest barrier to entry for any software reverse engineer. It is frequently used by both good and bad actors to protect their software from the peering eyes of reverse engineers. Because of this, I hope that these write-ups not only serve to highlight the flaws of these protections but also help to improve the quality of them in the future. I also hope that these write-ups help inspire future research and innovation in the field of software obfuscation as it is as important as it is obscure.

Setup

Tigress is the first virtualization-based obfuscator I wanted to start with because it is simple, accessible, and free. This obfuscator was primarily developed by Christian Collberg at the University of Arizona for research purposes. To start analyzing Tigress, I needed to install the obfuscator and create a sample binary to analyze. While the source code for Tigress seems to be fairly hard to get ahold of, the pre-compiled binaries can be downloaded by just about anyone. After downloading the binaries from here on a Linux machine, some light setup needs to be done. The home directory for Tigress needs to be set in the TIGRESS_HOME environment variable and added to the PATH variable as well. Instructions for this can be found in the INSTALL file included with the binaries. Tigress differs from most software virtualizers due to the fact that it's a source obfuscator. Instead of taking a pre-compiled binary as input, it instead uses the C source code of the program you wish to virtualize. Not only does it do that, but it also gives you the virtualized source code of the program after it's been obfuscated. I chose one of the sample programs included with Tigress---test1.c---to begin experimenting with. The original source code for test1.c can be seen below.

void fac(int n) {

int s=1;

int i;

for (i=2; i<=n; i++) {

s *= i;

}

printf("fac(%i)=%i\n",n,s);

}

void fib(int n) {

int a=0;

int b=1;

int s=1;

int i;

for (i=1; i<n; i++) {

s=a+b;

a=b;

b=s;

}

printf("fib(%i)=%i\n",n,s);

}

int main (int argc, char** argv) {

fac(1);

fib(1);

fac(5);

fib(5);

fac(10);

fib(10);

return 0;

}

As you can see, the fib function prints the nth Fibonacci number while the fac function prints the factorial of n. Now that I had a sample program, it was time to obfuscate it using Tigress. The final command I used can be found below.

tigress \--Environment=x86\_:Linux:Gcc:4.6

\--Transform=Virtualize \--Functions=fib,fac \--out=test1_out.c test1.c

Let me quickly explain the parameters I chose here. The first two parameters are fairly self-explanatory; I wanted the binary to be compiled for Linux in x86 using GCC. There are other options available such as ARM and Clang, but I just wanted a standard Linux x86 binary to analyze. The next parameter specifies the transformations to apply to the binary. Since I'm mainly focused on the virtualization techniques of these obfuscators, I will only select that option for now, but I may investigate the other forms of obfuscation in a future write-up as Tigress has many. The next parameter lets you indicate which functions you'd like to virtualize. I chose the two main functions in the test program: fib and fac. The final parameter just lets you specify the file name for the obfuscated source code. After running the command, Tigress spits out two files: test1_out.c and a.out. The first file is the virtualized version of the programs source code and the second file is the compiled version of the virtualized program (compiled with GCC, as specified). The obfuscated binaries and source code can be found here. Now that I had a binary to analyze, it was time to load it into IDA Pro and get started with the analysis.

Analysis

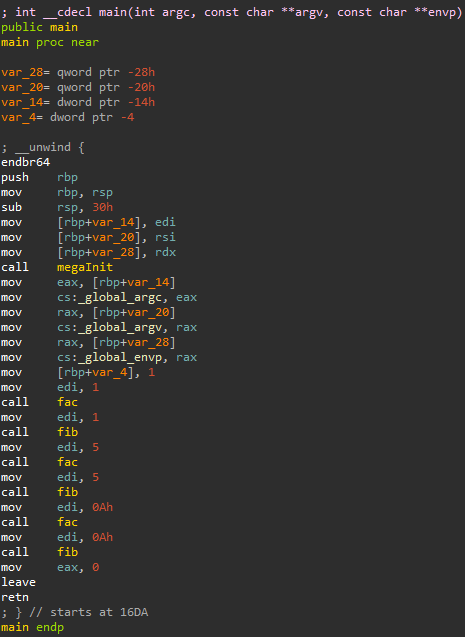

The *main* function of *test1* in IDA

Starting with the main function in IDA, it looked fairly normal. There's no obfuscation to be seen on the surface, so I decided to keep digging. A function that caught my eye from the start was megaInit. I assumed that it was going to be some sort of initialization function for Tigress, but opening it in IDA didn't reveal too much.

The *megaInit* function of *test1* in IDA

Source code for the *megaInit* function in VSCode

This function seemed to do absolutely nothing. Looking at the obfuscated source code (test1_out.c), I started to understand why. It was literally a blank function. While this function may not be used in Tigress for the virtualization transformation, it may be used for any of the other ones. Either way, I decided to ignore it. The next function to investigate is fac, the factorial function that I discussed earlier. This was one of the functions I selected to be virtualized while obfuscating the binary.

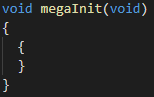

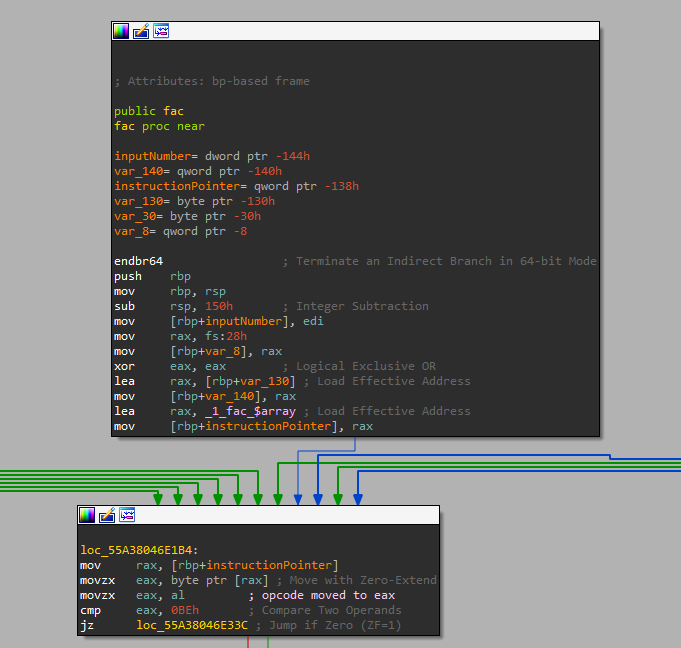

The fac function in IDA

Taking a quick look at this function, there is clearly something strange happening here. A small factorial function that was only 6 lines in the original source code has been expanded into a monstrous function with hundreds of conditional branches. We can assume that the virtualization-based obfuscation from Tigress had done its job.

VM Entry

The entry point of the fac function

When analyzing virtual machines (or most software for that matter), it's usually a good idea to begin analysis at the start of the function and work your way down to the complex parts. I started analyzing the virtual machine entry point for fac and found plenty of information about the virtual machine just by looking there. Starting in the first block, the inputted number for the function n is moved into rbp-0x144. I named this location on the stack inputNumber. This instruction also shows that Tigress is using the stack to store local variables for virtual machine context (and accessing them relative to the stack frame, rbp). After this, I looked towards the bottom of the first block. I wanted to find the location of the bytecode for the virtual machine. Since symbols weren't stripped for this binary, it's pretty easy to spot where it is. A pointer to data labeled _1_fac_$array is moved into rax. This register now stores a pointer to the start of the virtualized bytecode. Directly afterward, a mov instruction transfers this address to the stack variable rbp-0x138. This variable is now (fairly obviously) the virtual instruction pointer, so I named it instructionPointer. All of this incredibly useful information was gathered just by briefly looking over the entry point.

Virtual Stack

My next step was figuring out how the virtual stack was implemented by Tigress. Looking at the stack variables created in the entry point of the VM, there are 0x100 bytes allocated on the stack at rbp-130h. This immediately caught my attention as it seemed like an appropriate size for a stack. Also, a pointer to this location gets loaded into rbp-140h when the VM was initialized which is very likely a virtual stack pointer. Since there are no other large variables in the entry point, I started to assume that this was our stack. To confirm it, I needed to look at how rbp-140h was being used by the VM.

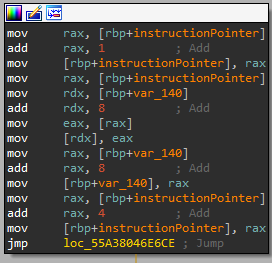

An opcode routine that heavily utilizes [rbp-140h]

To find out if this space was our stack, I decided to find an opcode routine that utilizes it. At the very start of the routine (shown above), the instructionPointer variable is being incremented by 1, meaning that my assumption was correct about this being the virtual instruction pointer. Since the instruction pointer was only incremented by 1, this is grabbing the byte after the opcode. This is likely an operand attached to the instruction that is used by the opcode handler. Afterward, rbp-140h is moved into a register, incremented by 8, and the operand is pushed onto the stack. After this completes, the stack pointer is incremented by 8 again, the instructionPointer is incremented by 4, and the virtual machine continues to the next instruction. From this routine, we can also see that the size of a standard instruction in this VM is 5 bytes: 1 byte for the opcode, then 4 bytes for an operand. Some of the instructions only use 1 byte as they don't need an operand, but I'll talk about that later. Also, since I've now confirmed that rbp-140h is the virtual stack pointer, I'll rename the variable to stackPointer.

One aspect of the virtual stack that is slightly unique is how it increments the stack pointer to push elements onto the stack instead of decrementing the pointer like a normal stack. This also means that the stack grows down instead of growing up like a normal stack. This doesn't change the functionality/usability of the stack in any way, but it's still cool to observe how the Tigress developers decided to implement it.

Local Variable Space

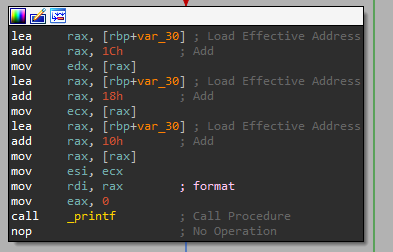

There is one more part of the virtual machine that confused me initially. Declared at the entry point, there is some space saved on the stack at rbp-30h. This seems to be a 32-byte space that is only used in one or two of the opcode routines. I needed to investigate these routines to see what they could possibly be used for.

A routine that uses the variable at [rbp-30h]

In this routine, it seems like 3 separate values are pulled out of this data space and loaded into registers. After this, the values are fed into printf. The only other instruction that uses rbp-30h pushes pointers to locations in the space into the stack. Through some assumptions, I concluded that rbp-30h is where local variables are stored. From now on, I'll refer to rbp-30h as localVariableSpace. I found this out by using the IDA debugger and looking at the values that are fed into printf. Referring to the original function, [localVariableSpace+0x10] is the "fac(%i)=%i\n" string, [localVariableSpace+0x18] is n, and [localVariableSpace+0x1C] is s.

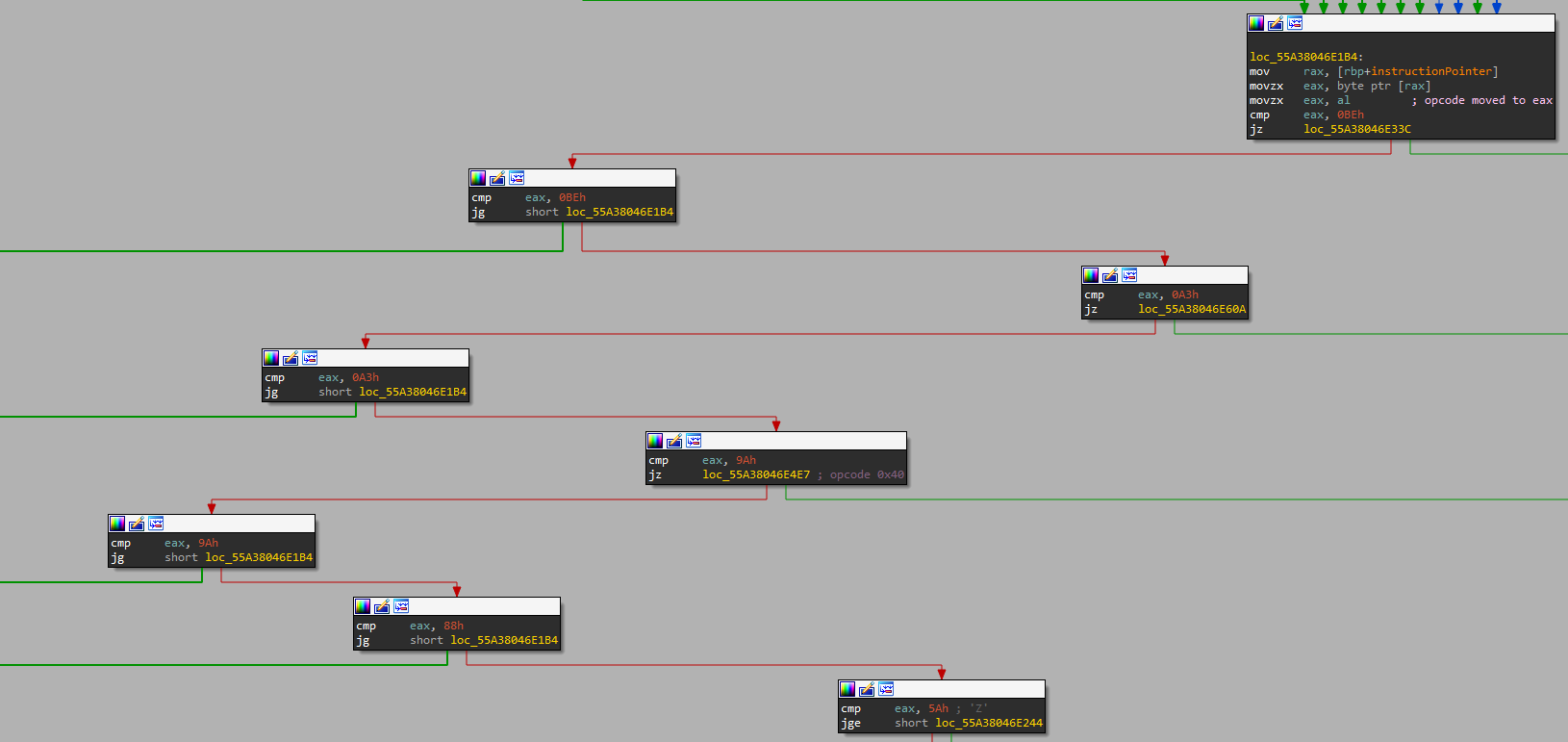

Dispatch

Now that I understood the virtual stack and local variable implementation, it was time to start analyzing the flow of the VM. After everything is initialized and the VM is ready to start executing, we get to the dispatch handler (shown below).

As you can see, this is an extremely simple dispatch handler. It mainly consists of long cmp chains that match an opcode to its specific handler. There's unfortunately not much more to talk about here. This is an incredibly simple dispatcher that leads directly to the opcode handlers with no further obfuscations. Now that we know this, let's look at the opcode handlers that this dispatcher uses.

Opcodes

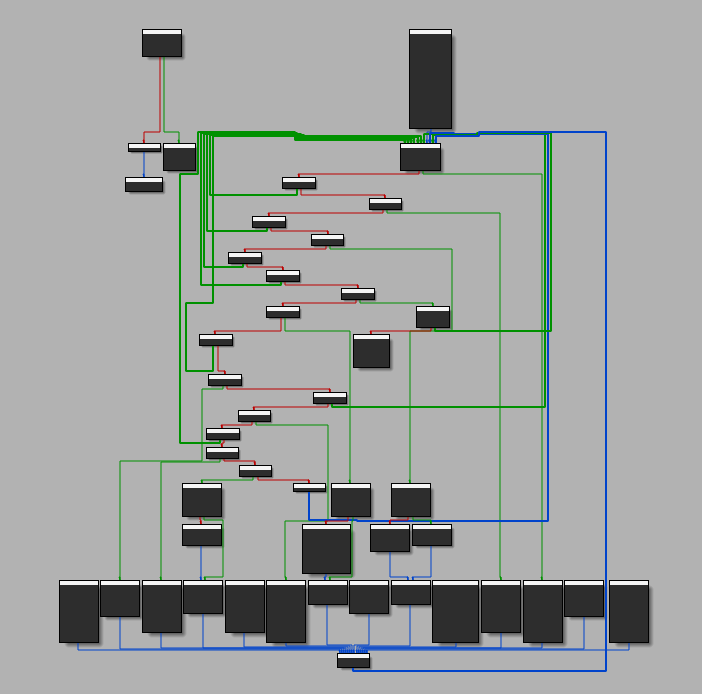

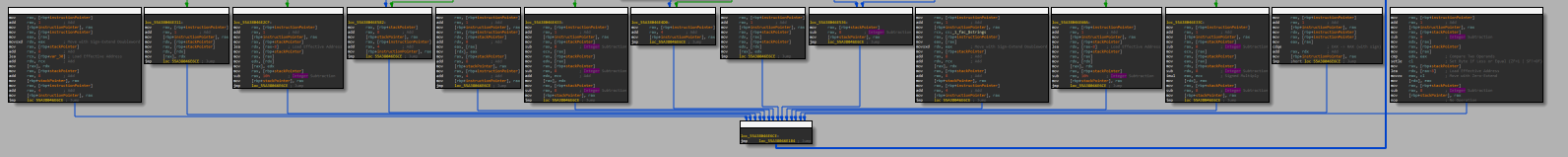

All of the opcodes for fac

Now that I was starting to understand the overall flow of the VM, I decided to start analyzing the individual opcode routines. I could count about 15 just by looking at the graph view, so I knew it wasn't going to be very difficult. Since the opcode routines are fairly boring to analyze, I'll save you the hassle and list out what each opcode does in the table below. Note that some of the instructions are only 1 byte in size because they do not require extra operands for their functionality. This is very similar to x86 machine code in that sense; each instruction can be a different size based on the need for extra parameters.

| Opcode | Size | Behavior | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0x1 | 1 Byte | Stores 4-byte value on the stack into an address on the stack | [[SP]] = [SP - 1] |

| 0x3 | 5 Bytes | Pushes a pointer to the first parameter (&n) onto stack | [SP] = &n |

| 0x7 | 1 Byte | Adds two values on stack | [SP - 1] = [SP - 1] + [SP] |

| 0x3A | 1 Byte | Moves a value on the stack into its same location (useless) | [SP] = [SP] |

| 0x40 | 5 Bytes | Feeds three values on the local variable space into printf | printf((LV + 0x10), (LV + 0x18), (LV + 0x1C)) |

| 0x5A | 1 Byte | VM Exit | retn |

| 0x5B | 5 Bytes | Instruction pointer jump | IP += [OPERAND] |

| 0x64 | 5 Bytes | Pushes a pointer to a local variable onto stack | [SP + 1] = LV + [OPERAND] |

| 0x67 | 1 Byte | Loads from an address on the stack | [SP] = [[SP]] |

| 0x7B | 5 Bytes | Pushes a pointer to a string in a string table onto the stack | [SP + 1] = StringTablePtr + [OPERAND] |

| 0x84 | 5 Bytes | Pushes an IV from instruction operand onto stack | [SP + 1] = [IP] |

| 0x88 | 1 Byte | Compares (<=) two values on the stack | [SP -1] = [SP - 1] <= [SP] |

| 0x9A | 5 Bytes | Jump to offset address from instruction parameters if value on stack is true (conditional jump) | if [SPv]: IP += [OPERAND] |

| 0xA3 | 1 Byte | Stores 8-byte value on the stack into a pointer on stack | [[SP]] = [SP - 1] SP -= 2 |

| 0xBE | 1 Byte | Multiplies two values on the stack | [SP - 1] = [SP - 1] ✕ [SP] |

One thing that is interesting about Tigress is its opcode randomization. In the other function that I virtualized inside this binary, fib, the instruction set is completely different. If I had to guess, Tigress has a preset amount of instruction implementations that it assigns to random opcodes while virtualizing a function. After it has its randomized instruction set, it likely just translates the x86 code directly. This is a simple yet effective implementation for these types of randomized architectures.

Instruction Trace

After I was done classifying all of the instructions, I started to analyze the actual virtualized program. I wanted to see how it utilized the virtual instructions to calculate a factorial the same way the original binary would. Similar to gathering info on the opcodes, this process is incredibly boring, so I'll just put all of the instructions in a table below as usual. I created this instruction trace using the Python 3 script found here.

| Instruction # | Opcode | Operand Bytes | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0x84 | 0x1 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes 1 onto the stack |

| 2 | 0x64 | 0x4 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x4 onto the stack |

| 3 | 0x1 | Loads 1 into local variable 0x4 | |

| 4 | 0x84 | 0x2 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes the constant 2 onto the stack |

| 5 | 0x64 | 0x8 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x8 onto the stack |

| 6 | 0x1 | Stores 2 into the local variable 0x8 | |

| 7 | 0x5B | 0x4 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Adds 4 to the current instruction pointer |

| 8 | 0x64 | 0x8 0x0 0x0 0x0 | (JT) Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x8 onto the stack |

| 9 | 0x67 | Loads 2 from address on stack | |

| 10 | 0x3 | 0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to the first parameter (&n) onto stack |

| 11 | 0x67 | Loads 1 from address on stack | |

| 12 | 0x88 | Sees if [SP - 1] <= [SP], evaluates false here | |

| 13 | 0x9A | 0xE 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Conditional jump to instruction 29, doesn't do it here |

| 14 | 0x5B | 0x4 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Adds 0x4 to instruction pointer, just goes to next instruction |

| 15 | 0x5B | 0x33 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Adds 0x33 to instruction pointer (jumps to instruction 31) |

| 16 | 0x64 | 0x4 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x4 onto the stack |

| 17 | 0x67 | Loads the value of local variable 0x4 onto the stack | |

| 18 | 0x64 | 0x8 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x8 onto the stack |

| 19 | 0x67 | Loads the value of local variable 0x8 onto the stack | |

| 20 | 0xBE | Multiplies local variable 0x4 and 0x8 and stores the result on the stack | |

| 21 | 0x64 | 0x4 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x4 onto the stack |

| 22 | 0x1 | Puts the multiplication result into local variable 0x4 | |

| 23 | 0x64 | 0x8 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x8 onto the stack |

| 24 | 0x67 | Loads the value of local variable 0x8 onto the stack | |

| 25 | 0x84 | 0x1 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes 1 onto the stack |

| 26 | 0x7 | Adds 1 to local variable 0x8 | |

| 27 | 0x64 | 0x8 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x8 onto the stack |

| 28 | 0x1 | Puts incremented local variable 0x8 back into local variable 0x8 | |

| 29 | 0x5B | 0xBE 0xFF 0xFF 0xFF | Jumps to instruction 8 (LOOP) |

| 30 | 0x5B | 0xB9 0xFF 0xFF 0xFF | Not Reachable |

| 31 | 0x7B | 0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0 | (JT) Pushes a pointer to the string 0x0 onto the stack |

| 32 | 0x3A | Useless instruction | |

| 33 | 0x64 | 0x10 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x10 onto the stack |

| 34 | 0xA3 | Puts string pointer into local variable 0x10 | |

| 35 | 0x3 | 0x0 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to the first parameter (&n) onto stack |

| 36 | 0x67 | Loads 1 onto stack from address on stack | |

| 37 | 0x64 | 0x18 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x18 onto the stack |

| 38 | 0x1 | Loads the value of n into local variable 0x18 | |

| 39 | 0x64 | 0x4 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x4 onto the stack |

| 40 | 0x67 | Loads 1 into local variable 0x4 | |

| 41 | 0x64 | 0x1C 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Pushes a pointer to local variable 0x1C onto the stack |

| 42 | 0x1 | Loads value of local variable 0x4 into local variable 0x1C | |

| 43 | 0x40 | 0x1 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Calls printf with local variables 0x10, 0x18, and 0x1C as parameters |

| 44 | 0x5B | 0x4 0x0 0x0 0x0 | Adds 0x4 to instruction pointer, just goes to next instruction |

| 45 | 0x5A | Exits VM |

For this instruction trace, I made the mistake of recording the trace for the very first call of the fac function: fac(1). This means that the factorial calculation code never actually runs, but I could still analyze it statically. For this reason, instructions 16-29 are all theoretical as I never observed the execution of them (the factorial of 1 is just one, obviously). It's still fairly easy to see how the virtualized bytecode relates back to the original program. We can see that local variable 0x4 is very likely the s variable (in the original code) and that local variable 0x8 is the i variable for the loop. We can also see that local variables 0x10, 0x18, and 0x1c are used as parameters for printf, which explains why local variable 0x4 gets moved into local variable 0x1C near the end of execution. This also explains why the string table value is loaded into local variable 0x10 as the first parameter to printf is always going to be the main string. With the loop code, it's fairly easy to see how this correlates to the original source code as well. It simply loads the value of 0x4 and 0x8 onto the virtual stack (variables s and i) and multiplies them together continuously until i equals n. All of these functionalities are extremely similar to their implementations in x86, so it seems like these virtual instructions are a direct conversion from x86 (like I guessed earlier).

Comparison Data

Throughout this series, I will put some charts at the end of each write-up to allow you to easily compare the different obfuscators.

General

| 🝰 | Tigress |

|---|---|

| Obfuscation Layer | Source Code |

| Architecture Type | Stack Machine, Randomized Instruction Set |

| Context Variables | Stored on stack and accessed through stack frame offset. Includes a local variable space, a virtual stack (and pointer to virtual stack), a virtual instruction pointer, and any parameters passed to the function |

| Dispatch Type | CMP Chains, can be changed in settings |

| Local Variables | Has its own space allocated on stack and accessed like an array |

| Virtual Stack | Grows positively, never needs to be resized |

| Static Obfuscations | None, can be changed in settings |

| Bytecode Encryption | None |

| External Functions | Creates an opcode that calls the function with local variables as parameters |

Strengths and Weaknesses

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| Free, Randomized Instruction Set, Incredibly Customizable | Relatively Simple VM, No Encryption, Only Works with C Source Code |

Conclusion

Tigress is a standard & simple virtualization-based obfuscator that is a great introduction into the inner workings of virtual machines. It uses a stack for most of its operations, a separate space for local variables, and implements instructions with simple, consistent routines. Since Tigress uses C source code as its input and output, it will likely be fairly different from most other virtualization-based obfuscators which use pre-compiled binaries as input and output. I am interested to see how they all differ in functionality and effectiveness. Even though there are almost no defining features that make Tigress difficult to reverse, the VM would likely be much more complex if I enabled more settings while obfuscating the binary. Even then, I'm sure that I'll get my fair share of complexity when I reverse some commercial obfuscators in the near future. Wrapping it up, the clean architecture of Tigress was great practice for future projects and I'm glad that I took the time to analyze it.